Over the years, I have come to see myself as almost as much a teacher of writing as I am of history. However, it has taken a long time for me to feel satisfied that I am doing this part of the job well.

In Key Stage 3 history at West London Free School, we alternate between ‘reading lessons’ and ‘writing lessons’ (see here). This means round half of our lessons are dedicated to planning and writing a single paragraph in answer to a question. I wrote about the structure of these ‘writing lessons’ in March, but – as you may be able to tell – I was not entirely satisfied: ‘My current approach is a big improvement, but it is far from the finished product.’

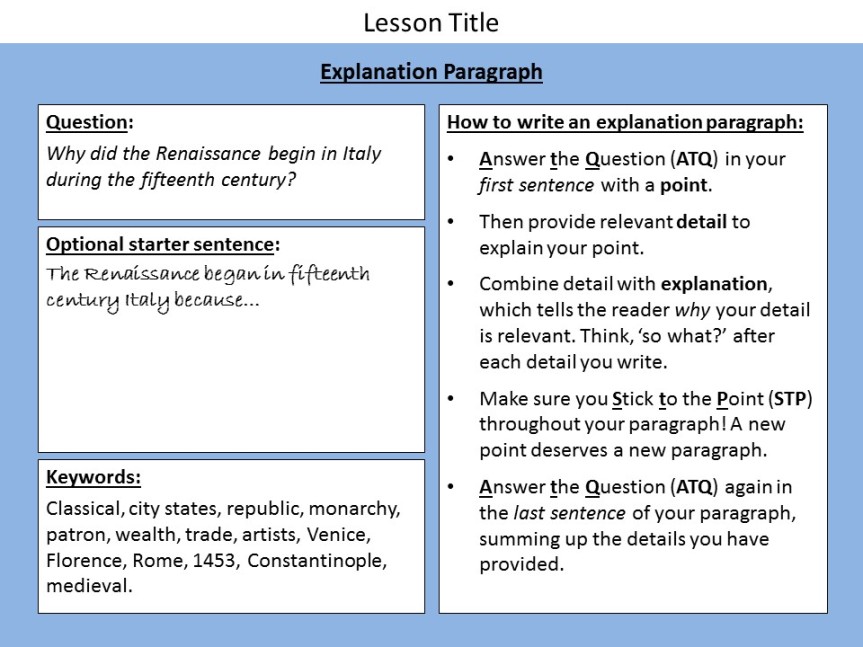

The problem with the lessons can be seen in the format of the slide below, which we were using last year. To be honest, it was a bit crap.

Problem A: Structure

The first problem was that ‘How to write an explanation paragraph’ box on the right hand side of the slide. I hoped that by having this appear every lesson, pupils would automatize the principles. Instead, each time I started recapping on these instructions, I could see pupils switch off and lose concentration. I was always explaining these instructions in the abstract, and – as Willingham writes – students struggle with abstraction. I needed to make the instructions concrete, by embedding them in real examples of pupil work.

Solution

Since September, in every writing lesson I have included an exemplar paragraph from the previous week’s writing lesson. We read it together as a class, and discuss what the pupil has done well. I consistently use the same annotations to ensure that pupils are being exposed to repeated examples of the same principles in different contexts, and internalising them.

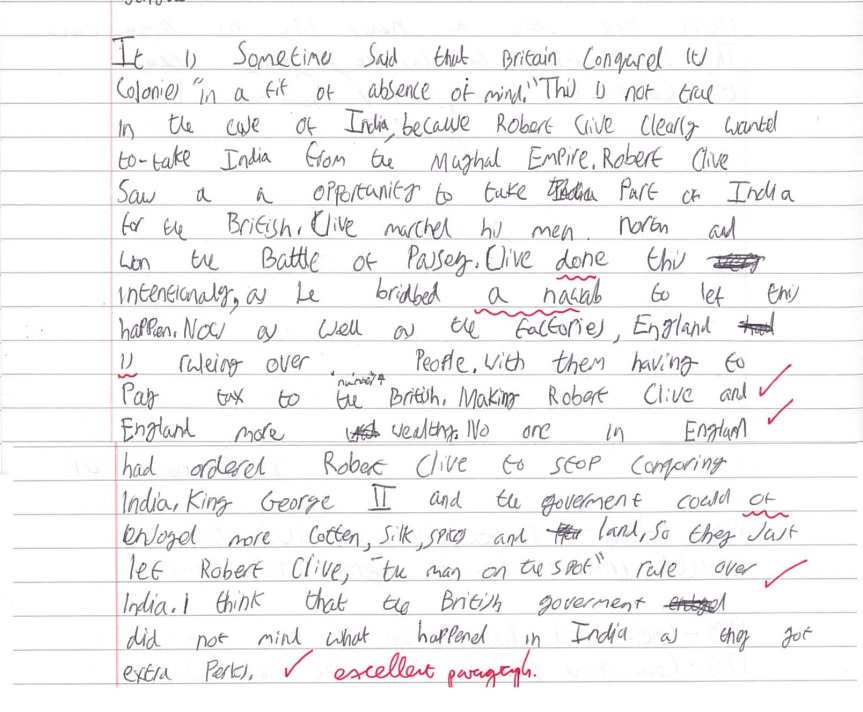

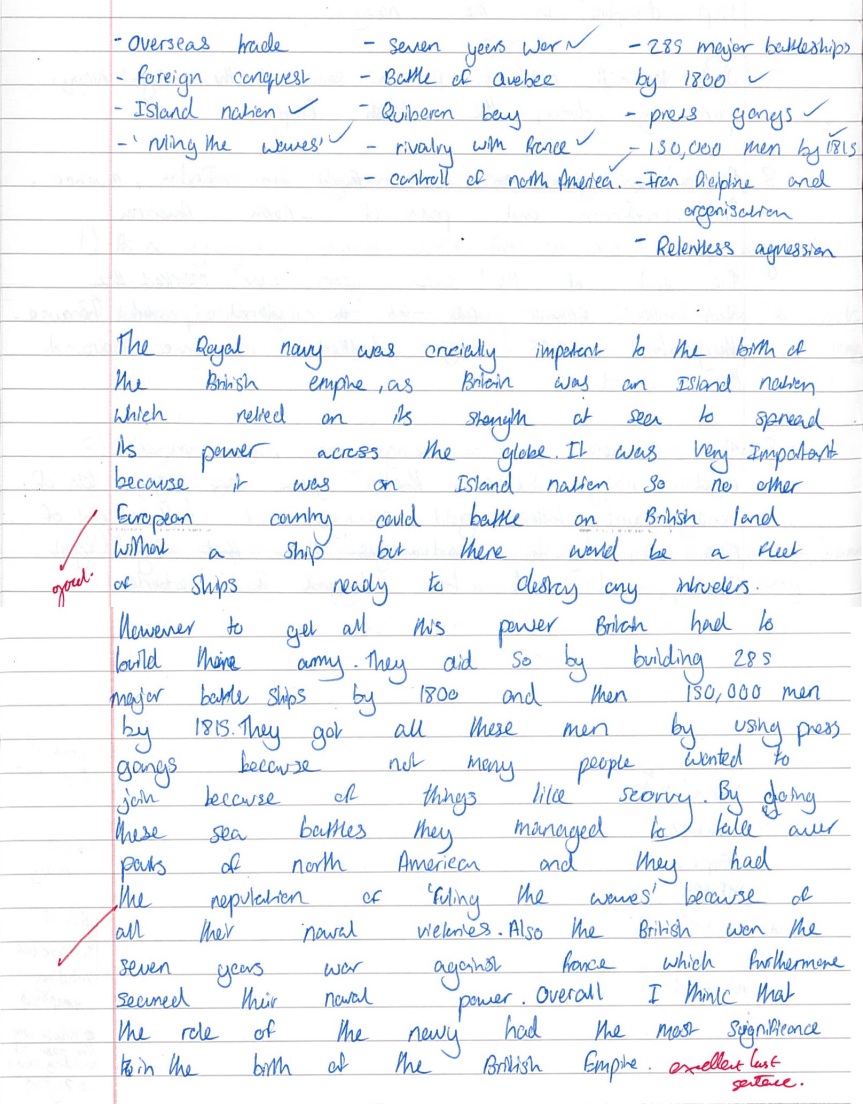

See below two examples from a unit our Year 9s have been learning on the Birth of the British Empire.

It is a bit of a faff going to the scanner each time you mark a class set of books, but it is proving hugely beneficial in ensuring our pupils understand how to structure their paragraphs. Whenever a pupil asks, ‘what do you mean ‘explain more’?’, I can immediately show a real and meaningful example of another pupil doing this well.

Problem 2: Vocabulary

Two experiences last year made me re-evaluate how fundamental explicit vocabulary instruction is for teaching historical writing. The first was attending Jim Carroll’s fascinating talk ‘Grammar. Nazis.’ at the Historical Association annual conference, and reading his article in Teaching History 163. I was particularly taken by his teaching of ‘lexicogrammatical chunks’ to his A-level class for ascribing significance to different causes of the Salem Witch trials: ‘decisive role’; ‘crucial factor’; ‘ultimate responsibly’ and so on.

The second was reading Isobel Beck’s fantastic book Bringing Words to Life (for a summary, see David Didau here). Beck breaks language down into three tiers of vocabulary:

- Tier 1: Everyday words that pupils enter school already knowing – ship, sea, country, war, danger.

- Tier 2: Words often used in written text, but rare in conversation – systematic, unprecedented, authority, prosperity, domination.

- Tier 3: Subject specific academic language – Aborigine, Mughal Empire, colonisation, mercantilism, treaty.

I had long seen the benefit of explicitly teaching Tier 3 vocabulary: most of my lessons have some historical ‘keywords’ and definitions. However, I always assumed that pupils would pick up important Tier 2 vocabulary incidentally. Of course, the great majority of pupils do not.

Tier 2 vocabulary is vitally important in history because it opens up new avenues of arguments that pupils are able to make. There are some arguments are simply impossible to make if pupils do not have the requisite Tier 2 vocabulary.

For example, last year I asked my pupils to write a paragraph answering the question: ‘Did the British intend to add India to its Empire?’ It is sometimes argued that the early stages of British colonisation in India were less by East India Company Directors or politicians sitting in London, and more by the ambitious officers in the East India Company – such as Robert Clive – who took advantage of the crumbling power of the Mughal Empire.

One’s ability to make such an argument is greatly enhanced by a working knowledge of the adjective ‘opportunistic’ (a classic Tier 2 word). The word ‘opportunistic’ was included in the textbook chapter on India, and I used it in my own explanations, but not a single Year 9 pupil picked up the word and made it their own in their writing last year. Passing reference was not enough – I needed to teach the word ‘opportunistic’ explicitly.

Solution 2: Vocabulary

Inspired by both Carroll and Beck, I resolved to place far more emphasis on vocabulary whilst planning writing lessons. Not just the ‘Tier 3’ historical keywords, but also the ‘Tier 2’ vocabulary which pupils are unlikely to pick up implicitly.

Therefore, I redesigned the slide we use in writing lessons. I promoted the ‘keywords’ box from a derisory portion of the bottom left-hand side, to bang in the middle of the slide, with a lot of surrounding space for me to annotate and add to words as we discuss them in class. And crucially, the box now includes a lot of Tier 2 vocabulary such as ‘trade’, ‘opportunistic’, ‘intentional’, ‘claimed [a territory]’, ‘systematic [killing]’ or ‘decrease’.

Prior to writing their paragraphs, I ask pupils to copy down these words into their books in three columns, as they appear on the board. This provides a clear opportunity to discuss the meaning and relevance of some of the most important words, and consider how pupils might use them in their arguments. I stress that pupils don’t need to use every word in the list, and certainly don’t need to use them in any particular order. But I do encourage pupils to tick off the words they do use as they write.

Conclusion

This emphasis on explicitly teaching paragraph structure and vocabulary to pupils has had a huge effect on the quality of their writing. And this simple change has made our writing lessons far more purposeful. I now enjoy teaching writing lessons as much as I enjoy content lessons – a bit change from last year.

Below are some examples of paragraphs from our Year 9 unit on the Birth of the British Empire. Purposefully, I have not uploaded paragraphs written by star students, who tend to write well-structured paragraphs with relative ease. Instead, they are taken from students whose written work has shown real improvements. Of course, some misconceptions and errors remain, but these paragraphs are far richer in detail and clarity of argument than their equivalents this time last year.

‘If you haven’t taught it, don’t expect pupils to know it.’ This is one of my guiding principles for teaching. For effective historical writing, explicit teaching of historical knowledge is necessary but not sufficient. We also need to teach paragraph structure and Tier 2 vocabulary. The approach outline above is – I think – the best I have found so far for doing so.

QUESTION: What motivated the British to settle colonies in North America during the 17th Century?

QUESTION: Did the British intend to add India to its Empire?

QUESTION: Did the British colonise Australia on purpose?

QUESTION: How important was the role of the Royal Navy in the birth of the British Empire?

Thank you for sharing. Although teaching year five, some of what you are saying is relevant. We have just been writing explanations. Had never thought about the 3 tiers of vocabulary before. Particularly like idea of first sentence answering the question.

Thank you.

LikeLike

This is great. As an English teacher there’s lots here that’s helpful.

One question – I noticed neither of the First Sentences do use the word ‘because’ as requested. Is that something that you no longer insist on?

Thanks,

Phil

LikeLike

Hi Phil. Well spotted! I always give permission to pupils not to use the suggest starter sentence if they feel they can write a better one. The two paragraphs I have shown as exemplars are from pupils who clearly felt they could! I do not say that every first sentence needs to use the word because, but suggest to any pupils who is struggling with ensuring their first sentence answers the question, using ‘because’ is a good way of ensuring it does.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thank you. I’ve been experimenting with suggested sentence starters and ‘rules’ with my classes and found myself telling students the same thing this week – if they feel they can improve on the suggestion then they are encouraged to do so.

I think that’s useful built in differentiation, where the less confident have the support in place and the more confident have the freedom to be intentionally creative.

LikeLike

Great article Rob thanks. Couldn’t agree more with your observation about expecting students to learn and utilise techniques if we don’t teach them explicitly.

LikeLike

Reblogged this on The Echo Chamber.

LikeLike